PORTHMADOG ARTWORK PILLARS BY HOWARD BOWCOTT 2025

Porthmadog played a crucial role in the development of the slate industry and the culture that it nurtured, so it is very fitting that this is celebrated in the four artwork pillars that are inspired by the heritage of the town. Together, the pillars create a sculpture trail around the town that reveals the history of each location and the specifics of each site. Perhaps the best place to start is the Harbour, the centrepiece of the series.

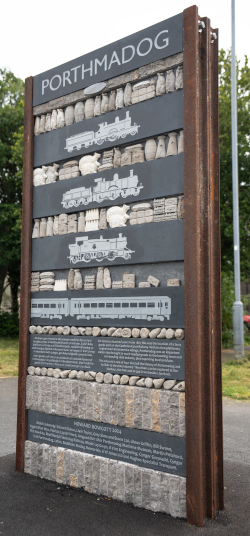

Pillar at the Harbour

These days the harbour is a centre of leisure and relaxation, but for nearly a hundred years, from the 1820’s to the outbreak of the First World War, Porthmadog harbour was a bustling, noisy centre of activity for the slate industry. The rattle of railway waggons brought roofing slates directly down from the quarries in the hills to the quaysides extending all along the harbour. Here the slates were stacked and stockpiled until the sailing ships that carried them all over the world could find sufficient space to enter the bustling harbour and load their precious cargo.

Many of these sailing ships were actually made in the local shipyards that took advantage of the tidal waters of the harbour. The sound of Welsh oak being sawn by hand and chopped with axe and adze filled the air, complemented by the ringing of hammers on steel chisels as skilled workers shaped ships and tamped tar and rope into waterproof joints. These small but sturdy sailing ships carried slates all over the world and brought back much need supplies to the quarries and towns all around Porthmadog. They were such beautiful shapes, too: their graceful lines cut through Atlantic waves with ease, yet held slates securely, tightly packed into their curving timbers. A gift to any sculptor!

The pillar, just around the corner from the Maritime Museum, references the waggon loads of roofing slates, the neatly stacked piles of slates on the busy quaysides and the building of beautiful ships in and around Porthmadog. (See if you can spot the mouse by the Ffestiniog Railway slate waggons!) Names of ports visited by Porthmadog ships all across the world are engraved in the stacked slates; many of the tools used to build the ships are carved in the slate bands. Visit the Maritime Museum and see if you can identify the tools that I reproduced on the artwork – they are all there in the museum, which tells this engaging history in more detail. Local sea captain Henry Hughes wrote extensively about this history in his books Immortal Sails and Through Mighty Seas.

My text in English engraved on the artwork reads:

Slates from the mountain skyline,

Delivered by the rattle of waggons on narrow steel rails,

Stacked tightly into curving ship timbers, shaped and built here,

Shipwright and slate packer in constant opposition.

Oak and tar sealing precious cargo through mighty seas.

Llinos Griffin provided the Welsh version:

Llechi o amlinelliad y mynyddoedd

Yn cyrraedd mewn wagenni’n sgerbydu mynd ar gledrau dur,

A’u llwytho’n dynn i ddistiau crymion y llong, a’u ffurfiwyd a’u hadeiladwyd yma,

Y seiri llongau a’r llwythwyr llechi mewn gwrthgyferbyniad cyson.

Derw a thar yn sodro llwyth gwerthfawr i’w lle

drwy’r moroedd mawr.

Pillar in the Park

Before the creation of the park in the 1850’s, this expanse of flat ground was used as ropewalks. Here fibres of Jute were laid out and twisted together into long lengths of rope, by people walking up and down wooden walkways. Porthmadog and the slate quarries all around had to be as self-sufficient as possible and the ever-expanding fleet of sailing ships visiting Porthmadog needed many thousands of metres of rope.

My text in English on the rope-side of the artwork reads:

Before the Parc, industry and activity in long rows,

Ropemakers weaving up and down narrow walkways,

Twisting fibres to connect Porthmadog with far destinations.

Llinos Griffin provided the Welsh version:

Cyn dyfodiad y Parc, roedd gweithfeydd yn rhesi hirion,

Gwneuthurwyr rhaffau’n gwehyddu ar hyd rhodfeydd cul cysgodol

Yn troelli edefynnau a gysylltai Porthmadog â phellafoedd byd.

The ships also needed vast amounts of canvas to be stitched into sails. Above the quaysides and in buildings such as the historic sail loft around the corner behind Cob Records, large sheets of heavy canvas were stitched by hand to create billowing sails that carried the ships to distant ports all around the world - just by catching the power of the wind.

The ships were crewed by small teams of local sailors and they had to be able to navigate their way to all these distant ports. A school of navigation was established at nearby Pencei, where mariners learnt to navigate by the sun and the stars. Look carefully between the slates that form the sky above the image of the sail and you might just be able to work out the configuration of the Plough and the North Star, laid out in white quartz pebble set into the slate strata.

Beyond the Parc, above busy quaysides,

Sail lofts and the study of navigation.

Heavy canvas pierced by thick thread,

Sun and stars stitched into filling sails,

Carrying slates all around the world.

Tu hwnt i’r Parc, ceir prysurdeb Pen Cei,

y llofftydd hwyliau a’r ysgol fordwyaeth.

Edau drwchus wedi’i hoelio i gynfas trwm,

Yr haul a sêr wedi’u pwytho i hwyliau hyderus

yn cludo llechi ledled y byd.

Pillar near the main station and Glaslyn Leisure Centre

The site of the third pillar was once a busy railway yard, full of noise and activity as steam engines brought freight and passengers back and forth. Porthmadog harbour was not big enough to cope with all the ships that were needed to bring materials, fuel and food to the quarries and the ever-expanding local population in the middle of the 19th Century. They were desperate for the Cambrian Coast Railway to be built from Shrewsbury to Porthmadog in order to truly develop the slate industry. In 1867 the Cambrian Railway finally made it to Porthmadog and beyond to Pwllheli.

This helped the growth of the slate industry and allowed Porthmadog to flourish: as well as bringing coal, timber, bricks and food to the area, it allowed the export of slate, wool, sheep and fresh produce to distant markets in England. As the desire to holiday beside the sea rapidly grew through Victorian times, the Cambrian Railway also brought the first significant numbers of holidaymakers to the area.

The station side of the pillar depicts all the goods that were carried on the Cambrian Railway over the years. Follow the panels of images down the column and you will see how the tourist market eventually outstripped the goods carried. The heavy Victorian trunks give way to more modern suitcases and eventually the goods dwindle to nothing with the growth of road transport and the petrol engine. The four locomotive images depict typical engines of their time, through to the modern diesel trains that currently work the line.

The Cambrian Coast railway connects communities with one another and is a significant aspect of contemporary life in the area. It is also part of the topography of the area: the considerable engineering features of bridges and embankments from Aberystwyth to Pwllheli via Porthmadog now form much of the coastline of the Cambrian Coast.

This link between communities and the shaping of our shared coastline comes to life in the shell shapes that define the coast on the map side. These shell shapes were made by schoolchildren of the nearby junior school Ysgol Eifion Wyn, using clay that I then cast into concrete. The shells going out into the sea reference the land spurs such as Sarn Badrig.

In English my text reads

Polished steel rails

Arriving and departing

Bridging rivers and distances

Defining a coastline

Connecting communities

Llinos Griffin provided the Welsh version:

Cledrau dur gloyw

Y cyrraedd a’r ymadael

Yn pontio afonydd a phellteroedd

Yn diffinio arfordir

Yn cysylltu Cymunedau

Pillar at Cob Crwn near Snowdon Street

Cob Crwn was built to contain the surge waters of the Afon Glaslyn after the Cob was built, with a view to it becoming an inner harbour should the need arise. Today it is a sanctuary from the bustle of Porthmadog and a haven for nature on the edge of the town. A walk along its length reveals wetland wildlife and mountain views.

My artwork pillar here celebrates this gentler aspect of life and the natural world at this location. The shells were once again made by the schoolchildren of Ysgol Eifion Wyn. The images of tidal marks, river flow and estuary include many crabs hiding in the seaweed – see how many you can spot!

The map on the pillar shows the whole area from Aberglaslyn down to the sea - the Traeth Mawr - as it was until William Maddocks built his Great Embankment (known as the Cob) in the early 19th century. Twice a day the waters of Cardigan Bay would come flooding in, changing the small hills into islands and the rockfaces of Tremadog into sea cliffs.

There were several small ferry crossing points but taking animals to market and most foot traffic meant wading through the mile-wide waters of the shallow river – see how many animal prints you can find engraved on the sandstone panel. As folks walked and waded they had to keep an eye for the return of the rising tide - crossing the sands at low tide was no simple wander on the beach.

It was the completion of the Cob in 1811 that resulted in the creation of Porthmadog and its harbour. The Cob claimed agricultural land from the sea and the road along the top initiated the settlement that became Porthmadog, whilst the waters racing out through the sluice gates created the depth of water that became Porthmadog harbour. Both town and harbour were soon to become essential to the development of the slate industry.

Twice a day

Shifting sands and salt splashed islands

Sea cliff heights above lapping waves

Before the great embankment

Ddwywaith y dydd ceir llanw a thrai

Y tywod a’r môr yn tasgu ar y creigiau

Ynysoedd yn esgyn o’r tonnau tyner

Cyn dyfodiad y morglawdd mawr